Fruits of labour nourish us – a nice idea, but does it happen? For John Prior of Leicestershire, his efforts held promise. Modestly ambitious, he found employment that suited his talents. He hoped for the rewards of a good reputation and a comfortable lifestyle.

In 1779, John Prior published a map of Leicestershire. This outlined fruits of labour at a county level by showing human use of natural resources.

A map’s ability to describe a society is limited. Indeed, those limits allowed the wealthy to read Prior’s map as a story of improvement with more to follow. Prior’s purpose was practical but his map reflected a worldview from which prosperous readers could gain satisfaction. On the issue of fruits of labour for the poor, the map stayed silent.

So, let’s look at Prior’s story in the context of the county he knew. Prior’s labours produced a harvest, as did the influence of trade and business on the landscape. Eighteenth century commentators saw prosperous workers as the better sort, an area’s chief inhabitants. Yet most seemed oblivious to some darker aspects of their society.

Part 1: Fruits of Labour: John Prior and his World

A World of Patronage

Born in 1729 at Swithland, Leicestershire, John Prior blossomed within the orbit of Joseph Danvers MP. Danvers employed John’s father to manage his house and land. In Parliament, Danvers usually voted with the Whigs and was noted for his plain, rough ways. At home, he treated Joseph Prior as a faithful servant and left him £100 in his will. It was like receiving a £25,000 bonus today. For a person who worked with the system, patronage could pay dividends.

Later, John Prior relied on a wealthy patron, though with looser ties than his father’s. He expressed his loyalty and hope of further support by adding to his patron’s prestige.

When Prior published his map, he dedicated it to Francis Hastings, Earl of Huntingdon, with the utmost gratitude and respect. The leafy design around the dedication included Hastings’ crest, topped with a coronet. It showed Hastings’ ancestral home, Ashby castle. Prior referred to himself as Hastings’ most humble servant. At the bottom of the design, alongside corn, fruit and coal, lay a mapmaker’s tools. Prior had completed his labours.

Prior’s flattery of Hastings was mainly pragmatic. In general elections Prior voted for the Whig candidate, though Hastings and a majority of Ashby’s freeholders supported the Tories. Whigs like Prior aligned themselves with the wealthy middle class. They believed in the constitution and monarchy but emphasised religious toleration and industrial progress.

but leaves out minor roads, rivers and mills.

Fruits of Labour from Mapmaking

John Prior hesitated to launch into making a map. On the plus side, the Society of Arts had awarded Peter Burdett £100 for his map of Derbyshire. Prior valued their approval and knew they sometimes rejected maps. However, mapmaking needed an investment which took years to produce a return.

In a letter, Prior said he took on the work as a tribute to Leicestershire’s gentry. Yet grief probably pushed him into a decision. Starting in 1774, he determined to fulfil the Society’s expectations for a county map and found 264 subscribers who paid a guinea each. He also employed John Whyman, a surveyor who’d assisted Burdett with mapping Derbyshire. Prior excelled at maths, so was well qualified to supervise Whyman’s field work.

In January 1778 Prior sent his manuscript to the Society. They’d stopped making financial awards, yet public recognition would help sell copies. Prior wrote to the secretary: I shall be exceedingly thankful for ever so small a sum.

Hastings wrote to the chairman, commending Prior’s map and good conduct. The Society considered the map, checked some of Prior’s angles and agreed he’d made a neat job of it. They gave him twenty guineas and a silver medal inscribed with the words: Leicestershire accurately surveyed.

John Prior’s World: his County’s Character

For the two years of the survey, Prior lived with Leicestershire. He didn’t simply record its features. He selected, ordered and tidied them. Occasionally he left out or misplaced a mill or lime works.

Prior showed houses of farmers and gentry. Major landowners owned elegant mansions in large parks with lakes and woodland. Prior downgraded some prominent halls by omitting their avenue of trees. Further down the social hierarchy, he depicted many halls as farmhouses.

By the 1770s, landowners had enclosed most open fields to provide pasture for livestock. Areas of woodland remained, but Charnwood Forest was a heath eroded by enclosures. Profits from changed land use increased, providing money to improve housing for the wealthy. Many prosperous farmers desired three storey homes with tall sash windows. As buildings in the landscape still show, minor landlords built larger houses with more stylish fronts.

Thus, the character of villages progressed. Prior indicated Anglican churches as prominent and ancient buildings. He also showed the shape of villages. Most had populations of less than five hundred, though a few approached a thousand. The town of Ashby-de-la-Zouch, had a market, ruined castle and 2,500 residents.

His map shows Breedon Hall as a farmhouse.

Leicestershire’s Fruits of Industry

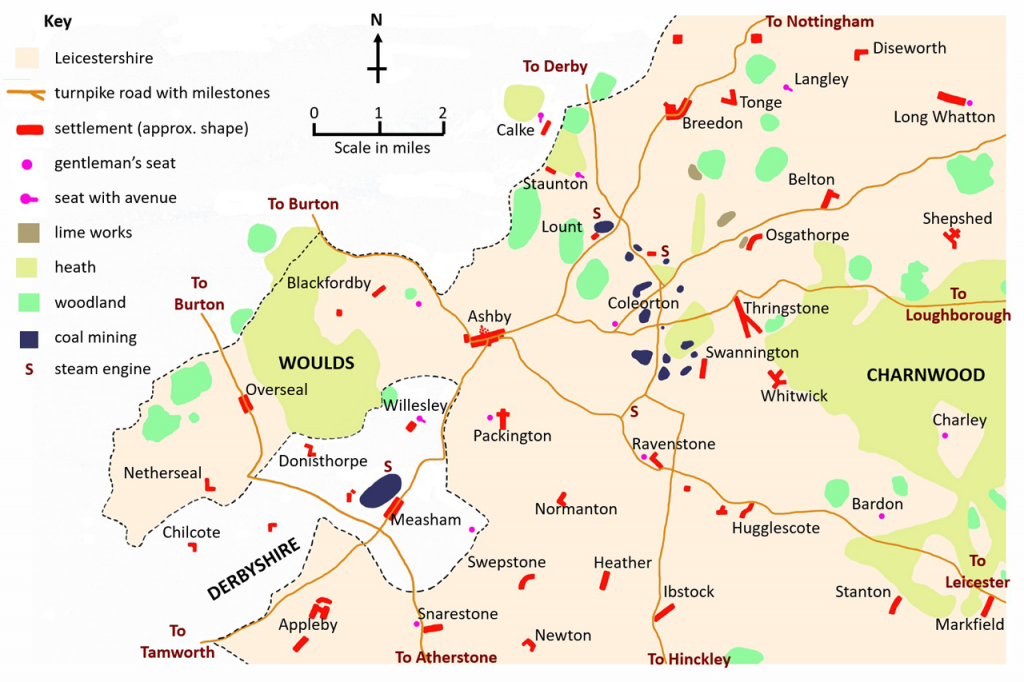

On Prior’s map, order and neatness mattered as much as accuracy. Those first two qualities became features of the landscape. Agricultural improvers tamed open fields with smartly hedged enclosures. Engineers and mine owners sunk shafts deeper with new techniques.

Wind and water mills with a medieval origin conveyed the idea that antiquity supported labour saving machinery. Prior drew many mills, though farmers around Ashby sold more cheese than corn. By the 1770s steam driven pumping engines drained water from some coal pits. These wonders of industry could do the work of 2,500 men with buckets. They dwarfed the effectiveness of ancient technology.

Increased trade in farm and mining products required better roads. Prior showed minor roads, but these developed so many ruts they limited journeys to walking speed. Thus, Prior highlighted roads maintained by turnpike trusts. A concentration of these around Coleorton improved dispersal of lime and coal.

Beyond its practical purpose, Prior’s map offered readers a sense of a tidy, productive world. Of course, no map could show the downside of modern practices. Yet land around Coleorton grew black, some who prospered wasted wealth, labourers remained poor.

Part 2: Fruits of Labour in Prior’s Life and Career

Back to the Beginning

Prior’s parents sent him to a small grammar school in Woodhouse. In time, its master came to rely on his understanding and character. So much so, when the master died in 1744, the trustees appointed Prior to the post. Aged 15, Prior gained accommodation within the school, ten acres of land and £14 a year. Parents who visited often mistook him for a pupil, and he found it hard to adopt an air of authority. In the schoolroom, he sat on a tall seat to magnify his height.

Prior’s reputation spread among local gentry. Several recommended him to Francis Hastings as a suitable master for Ashby grammar school. Thus, in 1763 Prior moved into its schoolhouse. Aged 34, he could now afford to marry Anne Cox of Quorn.

During forty years as master, Prior never had a pay rise. The school’s income came from property, let on leases of forty years. In 1767 rents amounted to £73, from which trustees paid for their annual dinner. Prior received £65. He had a free house but met the cost of any building repairs. Following a rent renewal process in 1799, annual income soared to £340. Meanwhile, inability to employ more teachers made the education Prior offered less attractive.

Practically minded parents looked for learning related to life’s main concerns, and Prior was capable of teaching a broad curriculum. However, the school’s Elizabethan statutes emphasised the study of ancient Roman authors in their original language. For a while the school flourished, but trustee inaction caused a decline in numbers of pupils.

Looking back, one former pupil felt Prior was kind. Certainly, he fulfilled his duties with some enthusiasm. He used the standard textbook for Latin grammar but created many improvements. Convinced of their value to students, he published an appendix without naming himself as the author.

John Prior Aimed for Self-improvement

While on a low salary at Woodhouse, Prior needed to earn more money. On the basis of his grammar school teaching, he began to lead church services. A local vicar, Richard Hurd, befriended him. They had a similar background, and Hurd was cultured and scholarly.

Hurd encouraged Prior to seek ordination, and recommended him to the Bishop of Lincoln. The bishop ordained him in 1759, and licensed him to a curacy in Rothley. Bishops normally tested candidates first to ensure their principles were sufficiently Anglican. According to a nephew, Prior’s preaching was thought-provoking and sensible.

Without a university degree, Prior could not expect to advance far in the Church of England. So, in 1762, he enrolled at a Cambridge college. After ten years’ membership, non-graduates could take a Bachelor of Divinity degree. Loose academic expectations and no need to live in college during term-time made this distance learning degree convenient. And Prior could afford the cost.

Although the university did little to support Prior, his love of reading and habits of independent study suggest he worked hard. After a final examination, he was awarded his B.D. in 1772.

Ashby’s vicar, Peter Cowper, had family in Chester and probably moved there in 1772. He continued to receive his income as vicar and appointed Prior as his curate. Generally, curates received under £50 a year.

John Prior Found Joy in Music

In addition to his skills in maths, Latin and theology, Prior delighted in the theory and practice of music. One Ashby friend, Dr Thomas Kirkland, admired the beautiful sound Prior produced with his violin. Kirkland, in line with his blunt way of speaking, blew into an oboe with determination and vigour.

Kirkland organised an annual music festival in which Prior took part. In 1774, it opened with Handel’s patriotic ‘Judas Maccabeus,’ performed in the parish church. Some choristers and soloists came from Lichfield and London. They took their audience on a journey from despair to the joys of victory.

Later, chief inhabitants of the area gathered in the concert hall next to Ashby’s castle. The orchestra played a few pieces and then for social dancing. Tickets for such events cost at least two shillings, more than most locals could afford.

The 1777 festival ended with a love story, Handel’s ‘Acis and Galatea’. Those available for a morning performance could experience, at second hand, a range of emotion: romance, jealousy, rage, and sorrow.

Prior loved music, and furnished his home to enable family and friends to enjoy playing together. In his will he left vocal music and instruments. The latter included a piano, harpsichord and virginal.

A Parallel Career for John Prior

Kirkland rented a pew at St Helen’s, Ashby. When the vicar died in 1782, he encouraged Francis Hastings to appoint Prior. Hastings admired Prior’s scholarship and praiseworthy behaviour. So, Prior gained £180 a year plus accommodation, though he continued to live in the school house. When he saw the shabby state of the vicarage, he rebuilt it before renting it out to increase his income.

Once when Kirkland met Hastings, the latter joked: Well, doctor, your friend the vicar, seems to be a poor preacher. Kirkland made a witty response. Neither man minded. For differing reasons, they welcomed dull sermons.

Prior hoped everyone would end up at one with God. He expected the best of humanity and of God. His calm preaching offered rational theology with an emphasis on good sense and moral practice. Prior helped listeners feel they were doing their duty and that God would reward them. In addition, he disliked superstition and religious controversy. He encouraged tolerance for differing beliefs.

Hastings disapproved of his mother’s Christian activism. She’d won favours for John Wesley’s followers and funded some congregations. By the 1780s, she rarely visited her Ashby house and allowed Methodists to worship in its laundry room. Hastings shunned religious enthusiasm, as did Prior. Thus, St Helen’s pulpit never shook with divine wrath to stimulate a dash for salvation.

Diarist John Byng spent a wet Sunday in Ashby in 1789, and considered attending an afternoon service. From a street near the church, he observed people walking both to St Helen’s and the Methodist meeting. He reckoned five times as many favoured the latter. Word was, the Methodists had fervour and devotion. At St Helen’s, there would be no preacher, and a charming organ had driven out the band and singers. Byng returned to his inn.

Further Advancement

At the age of 60, Prior taught himself Hebrew so he could read the Old Testament in its original language. Always keen to think through ideas, he studied academic theology and other literature.

In the wake of the French Revolution, Prior supported a government ban on rowdy meetings and seditious leaflets. Then, when France declared war on Britain in 1793, he and Kirkland contributed five guineas each to increase the county militia and form a cavalry unit. Such actions may have influenced Colonel Hastings of Willesley Hall to present Prior to the living of Packington. Prior gained another £180 a year, though he used part of it to pay a curate.

Fruit’s of Labour: Prior’s Family Life

When Prior’s wife died in 1774, he seems to have found comfort in work. Servants made his domestic life easier, and his widowed sister may have lived with them. Two of his three daughters never married. According to his nephew, their family life was contented and loving.

John Prior junior was ordained in 1788. He became curate at St Helen’s and later vicar of Willesley. Prior hoped the Hastings family would give his son a better living but in this he was disappointed. When he died, he left his children over £1,000 each.

Our view of Prior comes mainly from his nephew who found him industrious, cheerful and optimistic. Apparently, he thought more highly of his friends than of himself. He recognised his faults, was modest about his achievements, and didn’t push his views on others. In his will, he gave his soul to God’s mercy with hope.

In his final years, Prior suffered from kidney stones. Pain stopped him riding his horse, his normal exercise. Then, he had a slight stroke and his memory weakened. Although he taught up to a few days before his death, only a few pupils remained. He died in 1803, aged 74. The Derby Mercury described him as a tender parent and a truly good man.

In Conclusion: the Life of John Prior

The Unitarian minister, John Prior Estlin, wrote Prior’s obituary for the British Register. He spoke of Prior as his uncle, friend and the parent of his mind. Soon afterwards, the antiquarian John Nichols included Estlin’s obituary in his works on Leicestershire, minus the lines which identify its author.

For Nichols, Prior represented an example of enlightened character. Despite Prior’s modest wealth and farming origins, his values and contribution to the public good proved him a gentleman. Prior committed himself to learning, developed inner virtues, and cherished family and friends.

Prior’s patron, Francis Hastings, had died in 1789. He represented an older idea of gentility. Nichols pictured his mansion and traced his bloodlines through many noble ancestors. Indeed, Hastings believed his lineage deserved more recognition. He claimed he should be a duke.

Nichols courted gentry, hoping they’d buy his books, but also focussed gentility on personal qualities. Thus, he broadened the idea of a gentleman. None of this devalued Prior’s hard work and financial rewards. Indeed, to an area’s chief inhabitants, affluence appeared to stem from good character.

Prior’s map reflected a broadening of gentility in a different way. It showed more gentlemen’s seats than previous maps and equated farmhouses with the homes of minor gentry. Progressive work created wealth, and perhaps gentility too.

Nichols saw fruits of labour as both material and inward. By improving himself and his environment, Prior reaped a harvest of wealth and joy, dignity and modesty. Surely, suggests Nichols, Prior is an example to us all. Although gone from this world, does his legacy continue to nourish us?

Next: You may enjoy a Four Shires History article about South Derbyshire farmers and their secrets in the 1800s.

Leave a Reply