Across thousands of years, people have felt they’ve seen ghosts. Attracted to the idea, yet also sceptical, Charles Dickens included ghosts in his novels. Whether he portrayed them as real or springing from a disordered mind, his creations offered insights into the lives of those who experienced them. They drew out the feelings and attitudes of those they haunted.

Two centuries before Dickens, William Shakespeare used ghosts in a similar way. When Macbeth had Banquo murdered and then saw his ghost at a feast, he turned pale. No one else experienced the ghost, but they noted Macbeth’s odd behaviour. Banquo’s spirit opened a window into Macbeth’s guilt. Ghosts often say more about the living than the dead.

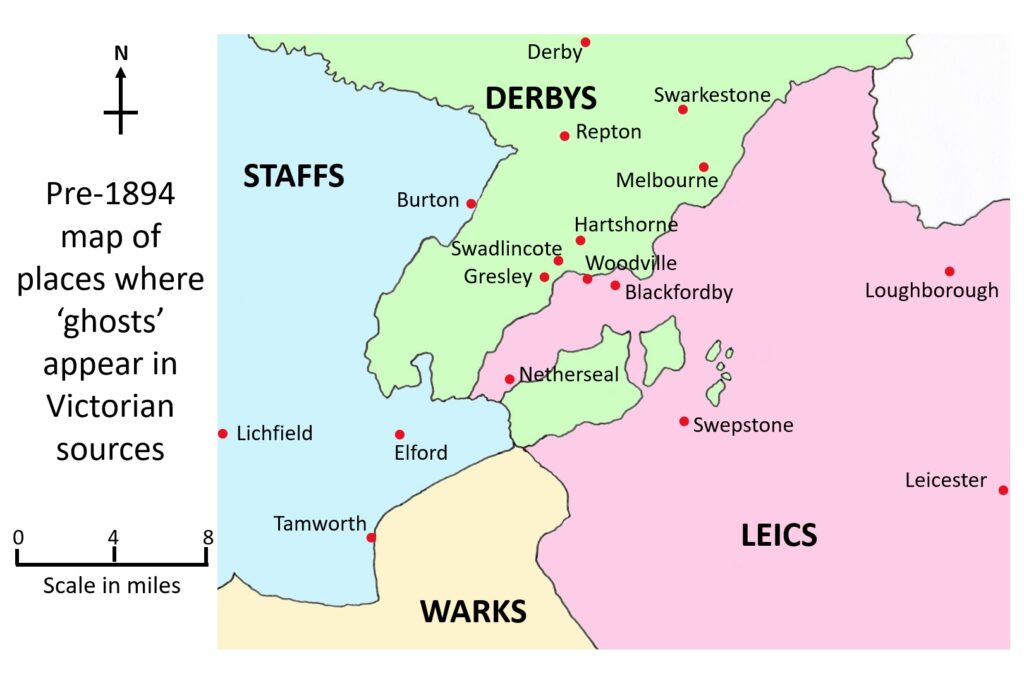

For ghost stories to shed light on a society, they need substance. I’ve searched Victorian newspapers for accounts of ghosts between Derby and Tamworth, Burton-on-Trent and Leicester. I’ve added a few memories I recorded in the 1980s, plus two stories from diaries. The number of usable stories is small, though I haven’t included them all.

Newspapers supported rational thinking. They shied away from ghost stories which claimed to be true. Thus, many tales of the period faded away. The ghosts of Swepstone Hall and Swarkestone Bridge dwindled to a mention. White Lady Springs at Castle Gresley, an industrial reservoir, lost the story behind its name. Indeed, Minnie Farmer, who drowned herself there in 1925, inherited the white-lady title.

Today, ghost hunts take place at Gresley Old Hall and other sites. Derby’s ghost walk includes a spot where a Roman soldier apparently still marches. Guides usually shun the word supernatural, speaking instead about imprints of psychic energy. In this article, I’ll use nineteenth century ideas and language. And I’ll explore the tension between mystical and seemingly rational notions.

Memories of Ghosts at Netherseal

Ghost stories stem from personal memories. Often, these are vivid in character. Here’s one from 1920s Netherseal, told to me by a participant in the action.

Many villagers tried to evade the peddler who knocked on their doors occasionally. One day, an apprentice at Dog Lane’s woodyard saw this salesman working his way along Main Street. He persuaded his fellow apprentices to play a trick.

When the peddler entered the carpenter’s shop, he began to display his wares: Buy these bootlaces; very strong.

On the stocks in front of him rested a coffin, from which a shrouded figure reared up. The peddler cried out, swept everything into his case, and ran.

The peddler didn’t have time to think: There’s a rational explanation for this. When surprised, his emotions kicked in. The trick worked because ideas about ghosts were common currency.

Over time, stories lose warmth and clarity. They become bits of memories pieced together. In the next story from 1920’s Netherseal, only the last section comes from a person with first-hand information.

Some girls wouldn’t work at Netherseal Hall as maids because strange things happened at night: rustling sounds, doors opening and shutting, a lady in a white gown on the stairs. Once, gloves on a window ledge vanished.

If a ghost haunted the Hall, what did it want? Perhaps simply to be remembered. In 1874, the dresses of two guests caught fire. Severely burnt, the girls died. It was an horrific story, both at the time and later.

Colonel Brazier-Creagh, the hall’s tenant, grew weary of ghost tales. One evening he and the rector watched in the entrance hall until midnight. The colonel held a loaded gun. He’d warned the household: if I hear a strange sound, I’ll fire. Did his materialist approach lay the ghost?

Opposition to Ghosts

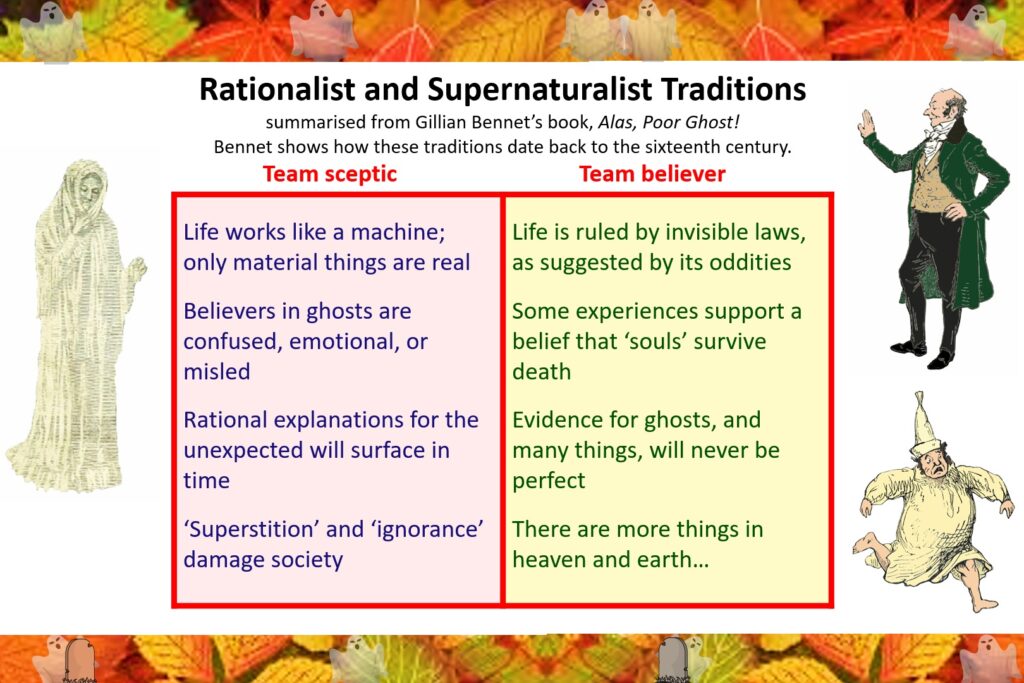

Various views about ghosts jostled each other across the nineteenth century. In the main, people were either believers or sceptics. However, the influence of amateur science led to the emergence of spiritualism as an independent perspective with roots in both camps. The old-fashioned view of ghosts as the devil in disguise appealed to a small minority.

In common opinion, ghosts were appearances of people who’d died. Whether restless souls or premonitions of death, they were elusive. Neither wholly visible nor material, they played on fear and anxiety.

Tricksters mimicked ghosts to amuse themselves at others’ expense. So, ghosts were intertwined with fraud and silliness. Yet belief in them remained resilient. Did this stem from acceptance of mystery? Or maybe, in part, disrespect for the opposition?

Educated opinion saw ghosts as superstitious nonsense. Belief in the supernatural irritated committed materialists. They didn’t merely consider ghosts a delusion; they sneered at believers and laboured to erase their beliefs.

In spite of huge social changes, rationalist and mystical mindsets stayed static. The first and last of the following materialist perspectives come from local newspaper editors, the second from a lecture by a Tamworth curate.

- 1798: Belief in ghosts arises from weak intellects which fail to realise they’re mistaken or victims of a hoax.

- 1892: Only ignorant rustics, who lack a manufacturing district’s education, believe in ghosts. The idea that spirits of the dead terrify the living is too horrible to accept.

- 1912: People who see ghosts should consult a doctor. If they hear noises in the night, they should examine the drains or lay down rat poison.

Many believers imagined ghosts with pointing finger and serious message. Aware of rationalist arguments and the possibility of a hoax, they were also suspicious. Thus, the tension between belief and scepticism played out within people’s minds.

The Ambivalent Message of a Leicester Ghost

One July evening in 1829, Mrs Bridgart’s family were in the yard at the back of their Leicester home. They heard a scream, coming from the house. The family ran indoors, and found their servant girl lying on the floor. She said: I heard a crash. I then saw a woman in white disappear through the ceiling.

Mrs Bridgart thought: A ghost is calling one of us to our grave. But was the girl playing a trick? She said to the girl: If thy heart condemns thee, speak the truth; God knoweth all things.

Quickly finding reasons to account for her experience, the girl said: God sent the ghost to frighten the boys. These were probably fellow servants. She told Mrs Bridgart: You don’t know how they swear and tell lies. And in what sounded like a premonition, she said: God won’t send the ghost again.

Mrs Bridgart felt the girl was wrong: the boys were good and helpful. But had a ghost foretold someone’s death? She continued to question the girl, and couldn’t make sense of her answers.

Eventually, she decided the girl wilfully upset the family, and sacked her. Still anxious about death, however, she began a private prosecution to force the girl to explain the ghost’s message.

Annoyed and mystified, the magistrates told Bridgart: We have no insight into omens; we cannot conjure up spirits! They concluded: the girl must’ve caused the disturbance; that’s the only rational explanation. They commanded her: Don’t play such tricks again.

No one addressed the fraught relationships in Mrs Bridgart’s household. The tension between the girl and the boys around relationships with their mistress, may have created psychological distress in the girl. If her ghost was an externalisation of an emotional crisis, her initial story might be genuine.

Two Genuine Accounts of Ghosts

Fraud may explain many accounts of ghosts. However, no one suspected it of Thomas Brittain who sent his son to Repton school in 1763. Soon afterwards, the boy caught a fever and died. He was eight years old.

Six weeks later, Brittain saw his son. It was mid-morning. His son looked the same as when alive. He said: Papa, I’m happy, and so will you be too. Brittain’s son then disappeared, leaving Brittain with a feeling of joy.

In 1776, Brittain told his story to The Ladies Diary. He believed he saw a disembodied spirit. A psychologist might call it a projection of the boy’s image and voice from within Brittain’s mind. That’s scientifically plausible. However, it probably wouldn’t ring true for Brittain, as it doesn’t for many today.

Explanations of a mysterious event sometimes contradicted the mindset of the person who experienced it. In failing to convince, rationalisations revealed their limitations.

As rector of Elford from 1835, Francis Paget visited the poor. In a book about his ministry, he referred to ‘Dolly,’ an elderly woman who told him she saw two corpse candles flickering near her cottage. She believed these will-o-the-wisps were spirits of the dead, calling her to her grave. Soon after, she and her daughter died.

Paget was an amateur scientist. Were these flames marsh gas which ignited spontaneously? Paget went to a boggy place, pushed it with his stick, saw bubbles emerge, and lit one with a match. He didn’t believe this gas could set itself on fire. And he’d seen flames moving around an Elford meadow; sometimes they made impossible jumps.

Paget concluded that will-o-the-wisps were spirits, but not fateful signs. Dolly’s sight of them and her death soon after was a coincidence, nothing more. Preoccupied with her own feelings, Dolly would probably block Paget’s explanation.

Attempts to Identify a Woodville Poltergeist

People’s interpretations of an experience rested on assumptions and biases as much as on evidence. False conclusions came easily.

Across two or three weeks in November 1878, large stones struck a clay miner’s front door between dusk and dawn. Aged 38, John Pickering lived in Woodville with his wife and seven children. Like most villagers, he believed some lout was annoying them. According to the Burton Chronicle, Pickering’s family were not disturbed on Sundays or when it rained.

Pickering failed to discover the culprit, and a minority of villagers decided the nuisance came from a restless spirit. In his history of ghosts, Owen Davies says that local gossip often linked persistent and undetected stone-throwing with a poltergeist. Soon, a group gathered each night in Millfield Street to see the ghost.

Interest focussed, not on the ghost’s message but it’s identity. One candidate was Roger the Swineherd who’d drowned in a quagmire on Ashby Woulds. Families with long roots in the area kept such legends alive. Possibly, parents threatened their children with Roger’s ghost if they misbehaved.

A second candidate for Pickering’s poltergeist was Nanny Kirk. In 1815, she left Blackfordby to get a pair of shoes mended in Hartshorne. She never came home, and no one could find her.

Weeks later, a labourer found Kirk’s gruesome remains in a field he was harvesting. Her body lay near a large beech tree, and was buried at Hartshorne. Its discovery aroused local feeling, and people named the beech: Nanny Kirk’s tree. In 1879, her tree was felled.

Was Pickering troubled by a poltergeist? I doubt it. Woodville’s rumour mill linked a cause of anxiety in the present with haunting incidents in the locality’s past. This historical resonance probably intensified local unease, like a bereavement awakening grief from previous losses.

The Great Derby Ghost Scare

In September 1885, Derby newspapers reported ghostly apparitions in several areas of the town. Some inhabitants feared to go out at night. Others walked the streets, looking for ghosts. A few sent letters of complaint to the chief constable. In the end, the police charged three youths with breach of the peace. The ghost scare turned out to be a scam in which various jokers played a part.

As a ghost story, this hoax revealed a range of attitudes to the supernatural. People made assumptions about what they saw in dimly lit streets, while gossip and the newspapers increased curiosity, fear and anger. Those surprised by ghosts responded in an instinctual way, guided by deeply rooted beliefs.

Responding passively to a ghost, a young woman fainted and took several weeks to recover. A telegraph messenger fled. As he ran, he shrieked: Fire! Murder!

An elderly laundress saw a gash on a ghost’s forehead. Its hands seemed clasped in prayer. She thought: Something dreadful has happened. She looked away. When she looked again, the ‘blessed thing’ was gone.

Other people’s minds jumped to mundane explanations. One man said of the ghost: He’s after the pears and plums in people’s gardens. A railway worker said: It’s nowt but an old white hoss.

Frank Grey confronted a ghost in Darley Grove. He said: Who are you, and what’s your game? When the ghost failed to reply, Grey clouted its ear.

Described in court as mild and inoffensive, Christopher Burrows pulled the linen off his head, drew a pistol, and threatened to shoot. Grey grabbed the pistol, and wrested it from him. Other lads appeared with sticks, one of whom struck Grey. The gang then chased Grey and his girlfriend down the lane.

A Different Kind of Ghost

The ghosts we’ve considered so far straddled the borderlands between deception, the mindset of believers, and the supernatural. Whether the latter had any reality was open to question. However, ghosts aroused genuine emotions, feelings of anxiety, menace and fear of death. Often, they reflected life’s dark side, giving some a reason to reject them.

Another type of spirit emerged in the late eighteenth century. Anton Mesmer claimed that an invisible fluid flowed through people and material things. A trained practitioner could realign this fluid, acting as a kind of magnet to improve mental health or produce sudden movements. The idea gained some popularity. It offered hope of evidence for a mysterious force within the machinery of life.

A craze for producing a magnetic effect on tables reached a peak in 1853. In Melbourne, a small table was put on a large one. Four people placed their hands on the top table, linking fingers and thumbs.

Ten minutes in, the table shook and crackled. After seven more minutes, the top table moved round the lower one, increasing in speed. Suddenly, the participants lost control; the upper table jumped to the floor.

John Briggs, a farmer and natural historian, recorded the event in his diary. Had magnetic influence really passed through them? Briggs repeated the experiment twice more. Nothing happened, not even after sitting for twenty minutes. Briggs now thought table moving a delusion. At a similar experiment in Duffield, however, participants waited for an hour before achieving success.

When Veritas wrote to the Derby Advertiser, he asked for the correct technique: Will a successful table-mover, tell me the rules I must follow? Whether experimenters wanted a clear procedure or quick results, they actively sought the ghost with the aim of pinning it down in some sense.

Belief in the Power of Human Minds

Many performers advertised their mesmeric skills to attract the paying public. When Annie De Montford visited Burton-on-Trent in 1877, she called herself the most powerful mesmerist in the world. Using the powers of her mind, she’d send volunteers from the audience into a trance and make them do amazing things.

The idea that mesmerism could entertain, appealed to ‘S’ of Church Gresley. In 1881, he wrote to a spiritualist newspaper of a potentially useful teenager: I can send him to sleep in a minute, but I can’t get him to do strange things. How can I mesmerise him to make good sport?

Serious minded performers believed mesmerism could improve lives or provide evidence of spirit-life beyond death. In 1871, a spiritualist offered access to a realm of mystery at Derby’s Corn Exchange. James Burns lectured his audience on the relations of mind to matter and soul to body.

Seventy-five minutes later, Burns’ hearers were more than ready for an illustration of spirit influence. Thus, Mr Morse, the great trance medium, began a lecture on the philosophy of death. From the point of view of the audience, all he manifested was an ability to speak without notes. This was not entertainment. People hissed and stamped their feet. At the end, they left in disgust.

According to Burns, spirit influence was similar to mesmerism. When mediums went into a trance, they received thoughts from spirits of the dead. As with telepathy, minds communicated without speech. And maybe science would prove it soon. Thus, a few vaguely scientific pursuits became receptacles for belief in spiritual or physical forces. This blurred the boundary between material phenomena and the occult.

Materialists soon added spiritualism to their hit list, alongside ghosts. They tried to discredit supernatural claims by supporting performers who played them for laughs.

Victorian Ghost Shows

Spooky stories worked best amidst winter bleakness. So, for Christmas 1863, the Loughborough Institute provided a ghostly entertainment in the town hall. Beyond giving pleasure, however, the middle-class organisers had a rational purpose. As the vicar explained before the show: Tonight’s spectral visitor is an optical illusion. Our amusement features ghosts produced by mechanical means. Thus, it’ll wipe supernatural beliefs from your minds.

Performers had used magic lanterns to produce ghost effects for years. By using smoke as a screen plus a ventriloquist, ghosts appeared in the audience and spoke. By fitting wheels to a lantern, ghosts startled people by lunging towards them.

Loughborough’s show used the latest equipment. A magic lantern in a pit below the stage focussed images of ghost-performers on to a carefully angled sheet of glass. The audience saw actors through the glass plus ghosts reflected from it.

In January 1868, Messrs Watson and Son’s Spectral Entertainment spent two nights at Lichfield, a week at Burton-on-Trent, and a fortnight in Leicester. They offered a sensational show with the most startling effects ever produced. These included a living head, floating in the air and singing.

As part of their repertoire, they performed The Haunted House, a short play in which a ghost drives an old man to drink brandy. The comedy reached its climax with a variety of ghosts arguing and fighting each other. The Burton Chronicle commented: Burton has never seen the like of this show before.

Ghost Shows as an Educational Tool

Materialist sponsors wanted stage magicians to discredit belief in the supernatural. They hoped people would stop believing in ghosts once they realised human ingenuity could manufacture them. As a tactic, this was naive. Performers relied on sensation to make a living, and entertainments captured the imagination. Far from fostering a materialist view, ghost shows probably prompted some to look for the real thing.

By defining superstition as evil, materialists fed prejudice against believers. To attract customers and pursue a purpose which was, in effect, mean-spirited, some ghost shows took a darker turn.

In 1895, Boswell’s Grand Circus visited Burton-on-Trent. It offered clowns, performing animals, and the Marvellous Steens. Snared in rumours of fraud in the United States, Charles and Martha Steen were touring Britain with their spiritualist entertainment. They offered a non-religious equivalent of séance-like activity.

Professor Steen placed a letter in the Burton Chronicle. He said: Two spiritualist mediums are coming from Birmingham to oppose me. If I can’t defeat them, I’ll give Burton charities £50. My scientific tricks can duplicate anything they can do. Thus, I’ll prove the supernatural doesn’t exist and all mediums are liars.

Steen’s money was safe. No spiritualists turned up to compete with him. He’d pulled off a publicity stunt. In spite of its inflated claims, his letter reflected the Burton Chronicle’s view. The editor supported demonstrations of human dexterity which eclipsed ‘trivial messages’ at seances.

During the Steens’ act, they revealed hidden secrets to loud applause. Indeed, Madame Steen made a prediction: the Burton Wanderers will defeat Wolverhampton. On the following Monday, this actually happened.

Spiritualists in the Burton Area

Opponents of the supernatural turned the debate between materialism and spiritualism into melodrama. Yet emphasising rationality and reality’s physical nature eroded enchantment and failed to satisfy. Many who sought a spiritual dimension to life glimpsed a middle way in mesmerism and telepathy. If two minds could connect with each other when their subjects were alive, perhaps mediums could communicate with spirits of the dead. Scientific proof of an after-life did not exist, but spiritualists might soon discover it.

In 1906, Burton’s Spiritual Evidence Society invited John Lobb to give a lecture. He’d published a book called: Talks with the Dead. Lobb said he’d seen hundreds of spirits, and he used ghost-photography to express what he saw. He told the meeting: Thousands of spirits fill this room. The spirit of Charles Spurgeon, the Baptist preacher, is right behind me. And the spirit of former prime minister, William Gladsone, recently told me: If I could return in the flesh, I’d work for peace.

The leaders of Burton’s spiritualists were colliery deputies, railway clerks, factory foremen. At least two belonged to the Independent Labour Party. Oscar McBrine, for example, sometimes stood in Derby’s market place and addressed a crowd for the town’s Socialist Society. His topics included: the right to work, mutual aid, survival of the fittest.

In 1911, Burton spiritualists launched a religious mission in Swadlincote. They believed in a God of love and valued the social environment offered by churches. Meetings in the town’s Labour Party rooms attracted between forty and eighty people.

A month later, residents of Swadlincote and Church Gresley formed their own Spiritualist Society. It’s president, John Sharpe, worked as a miner at Gresley colliery and led its ambulance brigade. Charles Poynton, a skilled pottery worker, trained Gresley Rovers Football Club. Fred Birkin was a painter and decorator.

Connecting with Spirits in Swadlincote

Much of the energy behind the Swadlincote society came from Emma Webster. A sewing machinist from Bradford, Mrs Webster and her grown-up son moved to Swad in 1906. Her promotion of spiritualism in the area met opposition. Many showed her contempt, yet she refused to give up.

Meetings at Swad aimed to instruct, help and comfort. Speakers often used the Bible in ways that fitted their beliefs. For example, they saw angels as souls of the dead, living in a higher sphere. Contact with these spirits brought love to anyone who needed guidance or comfort.

After the address, came clairvoyant tests. Mrs Webster and other mediums described impressions which came to their mind of people who’d died. If someone recognised a description, they confirmed it.

One evening, Mrs Webster said: Dolly Harrison’s here. This caused a sensation. A local character and midwife who’d celebrated her hundredth birthday, Harrison had been dead for thirty years. Many in the congregation felt joy in feeling her presence.

At the next meeting, Dolly appeared again. She asked Mrs Webster to place a chair for her beside the speaker, and apparently occupied the chair until the end of the meeting. Thus, Webster offered evidence of human spirits surviving the death of their bodies.

As an international movement, Spiritualism and its roots were complex. It also became tainted with fraud.

Locally, spiritualists blended science and mystery in the hope that their souls would continue to evolve after death. They formed communities of mutual care which showed love to those facing hardship in the material world. Their services included sermons and harvest festivals as well as clairvoyance. Spiritualists offered access to a safe and comforting spirit realm whose loving ghosts visited the imaginations of mediums.

Contrasting Views of Ghosts

People’s attitudes to ghosts revealed cracks in their dreams and rationalisations. Materialists thought ghosts a delusion. In their view, a person ceases to exist when their body dies. Although in itself a fair view, belief in the supernatural irked them. They opposed it, not simply to educate the masses, but because it challenged their neat and tidy perspective on life. Materialism felt good to those who adopted it. Their opposition to ghosts went over the top for personal as well as intellectual reasons.

Spiritualism offered a cosy perspective on the spirit world. Its ghosts were wholly good, mirroring the Enlightenment view which identified spirit with reason. In reality, darkness lurked both in individual psyches and communities. Negative emotions and motivations brought fear and harm.

Wild ghosts challenged comforting views. Some people faced a negative energy, even within their bedrooms. At Asfordby rectory, a ghost disturbed guests who slept in the spare room by pulling off their sheets and blankets. Was this long-running saga due to a practical joker, bad dreams, or creaking floorboards? Rationalisations did not always convince.

In 1911, the year of Swad’s spiritualist mission, a household in Burton grew fearful. When they went to bed, they heard raps on the panelling which covered the walls. Suddenly, the bedroom door flew open, not just once but repeatedly. The occupants experienced this night after night. They tried to wedge the door open; it didn’t work. A carpenter in the household removed some floor boards and replaced them. Eventually the disturbance ceased.

Then, in January 1912, a family member grew seriously ill. The raps started again. The same door opened of its own accord. In the morning, the sick person died. The family moved out.

Conclusion

Tales of ghosts employed imprecise language, science without rigour and intuitive interpretations. They also belonged to a broader context in which fortune tellers, astrologers and phrenologists thrived. Fraud embraced pseudo-science and the occult, both as a means to make money and for the fun of playing tricks. Thus, ghost stories aroused both scepticism and curiosity.

Those who held clear-cut views faced contradictions and events they couldn’t explain. In spite of opposition, hauntings and premonitions still happened. Individuals experienced strange and unsettling phenomena. Those who adopted a one-dimensional view of life found ways to smother complexity but it kept breaking in. Mystery and messiness remained, and within it lay energies many hoped would stay hidden.

Victorian society offered a diversity of strongly-held views on life. And many individuals held conflicting beliefs. To those who were sure they understood reality, other people’s opinions seemed irrational. Yet people’s beliefs, vague though they often were, helped them accept tragedies and make sense of a fast-changing world.

Annie de Montford said: The mind governs the world, meaning the controlling, rational mind envisaged by mid-Victorian science. However, no mind works that coherently. Within human minds there’s instability, disunity and repressed negativity. If human minds govern the world, maybe that’s the scariest ghost story of all. Even if every ghost story is of the mind, such a perspective brings no relief. The elusive energies which scared and attracted many Victorians, bubble up in modern societies too.

Leave a Reply